While flipping through Hugh Gusterson’s book, Nuclear Rites: A Weapons Laboratory at the End of the Cold War (1996), a chilling paragraph caught my eye:

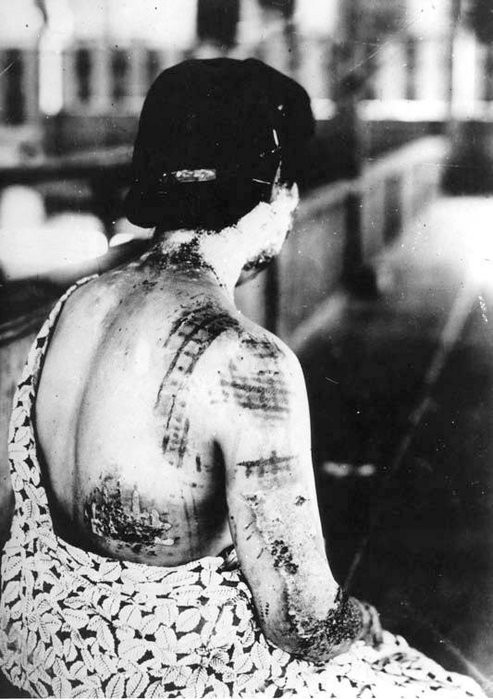

The marked bodies of all these pigs, dogs, monkeys, cows [subjected to radiation to study nuclear weapons effects], and people helped to produce a body of knowledge about the bomb. These mammalian bodies have served as texts from which to read the precise nature of the bomb’s power and have thus been indispensible in constructing the regime of simulations that has grown up around nuclear weapons. (108)

In just a few lines, Gusterson, who dedicated a life’s study to understanding the cultural ripple-effects of the nuclear age, laid out one of the most horrifying symptoms of the bomb: scientists studying each irradiated species like a book, hoping that mapping wounds would pave the path towards scientific enlightenment. All of it done in the name of discovery, to find the optimal means of inflicting damage and stay ahead of the arms race. Despite the horrendous act, scientists were spellbound by the prospect of scientific progress. So onward they pressed, looking through the person, past the soul, to study the flesh.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings are commonly associated with grim visuals of the mushroom cloud, the remnants of the Genbaku Domu (Atomic Bomb Dome in Hiroshima), shadows etched on pavements by thermal radiation after the initial blast.

But where science destroys, art defiantly restores. While scientists studied test subjects, Japanese artists sought how to preserve and convey the intangible — stories of loss, helplessness, and anger —, and interpret how the atomic attacks deeply affected the social, political, and cultural landscape of postwar Japan. The artist’s voice is a critical, but often overlooked, piece of the nuclear narrative.

***

Three years later, thumbing through the pages of a friend’s art book titled Little Boy: The Arts of a Japan’s Exploding Subculture, I found a still from one of Studio Toho films, “Matango” (1963). It showed a horribly disfigured man — boils all over his body — standing in front of a doorway as if to reveal the full extent of his monstrosity. Draped in blood red light for dramatic effect, the man’s worst deformity is on his head, which resembles a sprout of mushrooms. Studio Toho, lauded as a leader in tokusatsu (loosely translated as special-effects filming), created a series of monster movies focusing on a theme of human mutation inspired by the nuclear bombings. Another famous monster, “Godzilla” (1954), emerged out of the Japanese imagination 9 years before “Matango” and became one of the most popular nuclear-inspired cautionary tales on Japan’s silver screen. Both films feature monsters borne out of freakish mutations that eventually upend Japanese society — a recurring theme in Japan’s postwar art.

The aftershock of defeat and destruction after WWII was a cultural and artistic awakening for Japan; the postwar aesthetic gravitated towards a blend of the grotesque and the cute (“kawaii” in Japanese) to reflect the trauma and frustration of a country and its people. While the act of bombing took away humanity, the experience of being bombed seemed to amplify it; pop art became a platform for Japanese artists to form an understanding of victimization and loss. It also captured the unquantifiable consequence of nuclear warfare, the cultural and social toll of dropping the bomb.

Japanese postwar art is eerie, defiant, and loud. One of its pioneers, Taro Okamoto (1911–1996), captured it perfectly with his “ART IS EXPLOSION!” cameos on Japanese TV commercials. “ART IS EXPLOSION!” became Okamoto’s trademark statement, which resonated strongly with the art world as Japan enjoyed rapid economic growth while grappling with the political and social ramifications of its devastating loss during WWII. Okamoto’s sculptures and murals also mirrored his trademark statement, often mixing brilliant colors and morbid scenes, Okamoto’s pieces and the production of “Matango” are just some out of many artistic interpretations borne out of the nuclear age. What is striking is their interpretation of their humanity — how to cope and move forward after a national shock and tragedy.

Sixty-six years after the first nuclear bombings, another nuclear tragedy struck Japan, this time in the coastal Fukushima prefecture. The footage was hard to stomach: an earthquake-induced tsunami waves towering more than 10 meters high swallowed cars and crashed over the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station’s seawall, which shut down AC power supply in Units 1–5. as it submerged emergency diesel generators that was supposed to act as backup (this made all emergency cooling systems unavailable except for the Reactor Core Isolation Cooling (RCIC) System). On March 12, 2011 — a day after the tsunami collided onto Fukushima Daiichi — a hydrogen explosion occurred in Unit 1 and a series of unfortunate events occurred, contributing to the amount of radiation released in the area (specifically, the radioactive isotopes Cesium-134, Cesium-137, and Iodine-131 according to a February 2014 report on lessons learned in radiation protection).

Naturally, the Internet lit up with curious, confused, and frightened reactions, from anti-nuke protests in Southeast Asia to food contamination scares among kale/tuna-loving communities in California. Amidst the flurry of expert opinion and public (mis) information, Japanese artist Hachiya Kazhuhiko’s animated short “Nuclear Boy” (2011) became a seminal contribution to the greater public’s conversation on the Fukushima accident. It tells a story of Nuclear Boy’s stomach problems and the Japanese community’s quest to help him get better before he…poops (the euphemism for a massive meltdown and significant release of radiation). The animation admits that Nuclear Boy farted a couple of times — some close calls — but that doctors (workers at the plant) tirelessly worked to prevent the boy from going #2.

The magic of “Nuclear Boy” is the humanity it brought back to the conversation. Kazhuhiko’s narrative intentionally departs from the technicalities of the accident in highlight and amplify the emotional weight of having to carry the burden a nuclear disaster while everyone else in the world watched in the comfort of their homes. Kazhuhiko readily admits that he is no expert in nuclear matters, and that “Nuclear Boy” is a product of art and family. Since then, a handful of Japanese artists have contributed to the body of work inspired by the Fukushima accident, each showing a different range of emotion and shade of humanity.

The human bond that emerges after tragedy is powerful. Its strength lies in emotional connection and the comfort of a common narrative after the shock and awe. While scientists recorded histories through data points and talking heads regurgitated buzzwords and factoids, artists took charge of restoring the best of us during our most destructive and defeated moments. It is an act of going through the fire, painting the landscape, and remembering it fiercely for centuries to come.