*This piece was written by Sayaka Shingu, a former student at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies. Lovely Umayam edited and published this piece on Bombshelltoe on March 3, 2013.

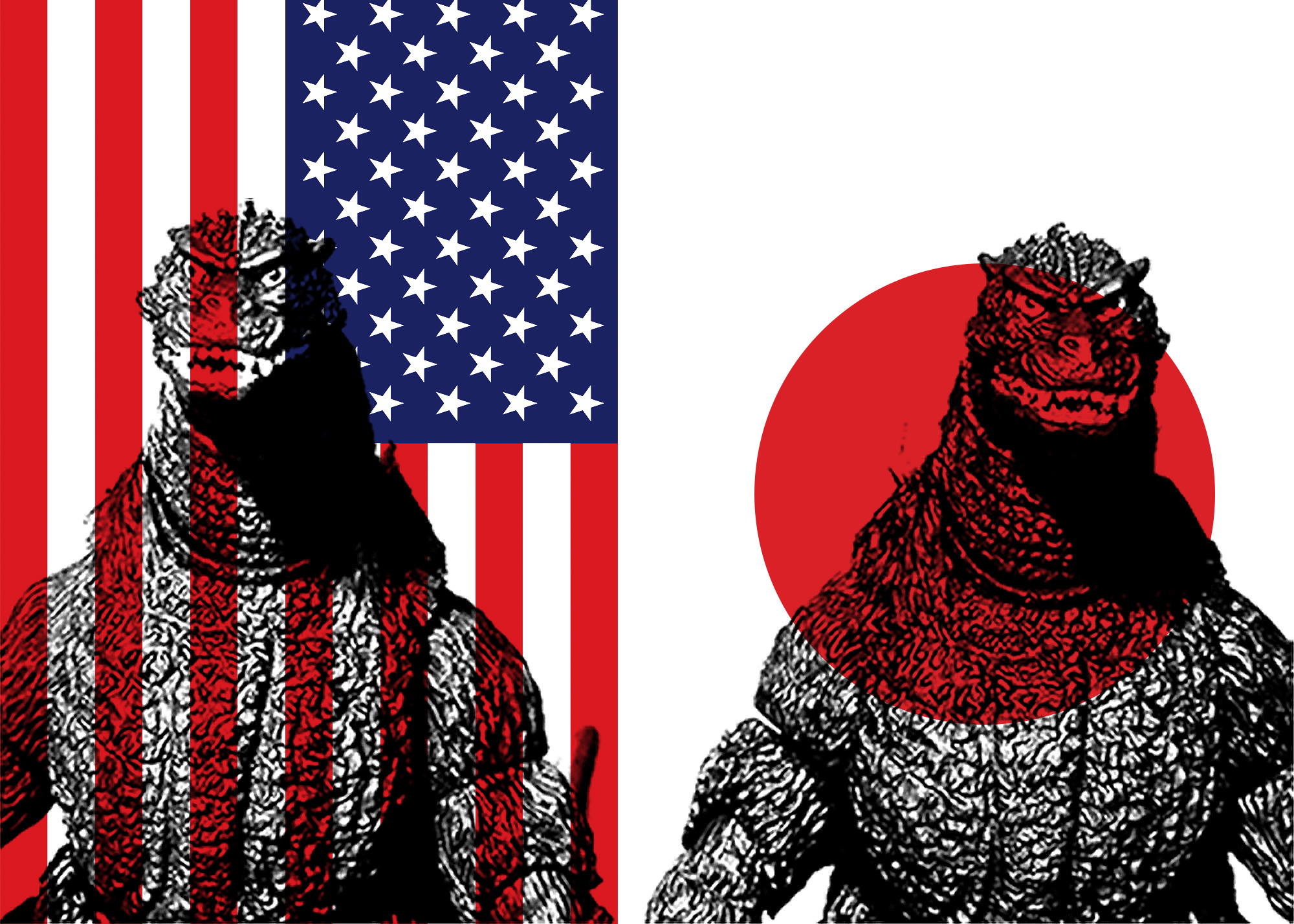

A decade after the Hiroshima bombings, the effects of nuclear disaster re-emerged in Japan’s popular consciousness as Gojira (ゴジラ), a mythical beast awakened by a hydrogen bomb test. Gojira is one of the awesomest monsters to plague mankind on the silver screen, but multiple remakes have inadvertently re-interpreted his nuclear narrative.

Let’s re-visit Gojira’s nuclear genesis as told by the Japanese classic. In 1954, a US hydrogen bomb test on Bikini Atoll contaminated a Japanese fishing boat, Lucky Dragon Five, which in turn inspired the Japanese movie company TOHO to produce Gojira.[1] Gojira is a product of nuclear testing-gone-bad: a giant lizard with festering skin, incandescent laser powers, and radioactive breath attacks Japanese citizens until a newly invented weapon called Oxygen Destroyer (which is somehow more powerful than a hydrogen bomb) defeats him. The end.

Well… not quite. The 1956 U.S. version of the Japanese classic subtly and perhaps unknowingly re-imagines the story of our lizard enemy.

Several years after the premier of the Japanese Gojira, America’s Godzilla—King of the Monsters! went on production.[2] Producers edited the original Gojira to include a US perspective as told by a new protagonist, Mr. Martin. The US version has Mr. Martin reporting an incident of Gojira in Japan without translating the original Japanese dialogue except for some important scenes in the storyline. For the most part, American audiences observed Gojira’s attacks in Japan through the lens of Martin.

In 2004, roughly fifty years after the first American remake of Gojira, the Japanese original was eventually released nation-wide in the US with English subtitles and no edits. This brought to light that the 1956 US Godzilla edited some pretty important scenes in the original 1954 Gojira, leaving out interesting Japanese perspectives on nuclear testing.

Edits made on the last scenes of the classic is a perfect example. In the original Gojira, after the Oxygen Destroyer defeats Gojira, Dr. Yamane remarks,

I can’t believe that Gojira was the only surviving member of its species. But, if we keep on conducting nuclear tests, its possible that another Gojira might appear somewhere in the world, again.

He cautions viewers about the consequences of repeated nuclear testing, which could cause a similar tragedy to the contamination of Lucky Dragon Five. This is obviously a warning towards the imminent threat of nuclear devastation as humans continue to dabble with nuclear weapons technology.

Interestingly, Dr. Yamane’s debbie-downer conclusion completely disappears in the 1956 version. Instead, the movie ends with Mr. Martin’s upbeat lines:

The whole world could wake up and live again.

Yay! Happy ending! The new high-tech weapon Oxygen Destroyer successfully eliminated the global threats and saved mankind.

Why did the 1956 Godzilla exclude Dr. Yamane’s warning? Considering the fact that the 1956 Godzilla used some important scenes from the original Japanese movie, it would have been quite simple to include such a poignant scene. Perhaps the editing was necessary to satisfy the palette of American audiences. But leaving out this particular scene – and ultimately changing the tone of the ending – gives us two divergent perspectives towards nuclear testing from two countries that experienced the nuclear age in very different ways.

For Japan, the Lucky Dragon Five incident was another painful reminder of nuclear devastation, which in turn escalated fear towards nuclear fallout, food contamination, and other side effects of nuclear testing. Perhaps the 1954 Gojira captures the ways in which the Japanese public viewed nuclear catastrophe as something that can happen over and over again. After all, Japan experienced nuclear tragedies through war and testing. And with such harrowing experiences, people were likely to believe that anyone can be a victim, anytime.

For Japan, the Lucky Dragon Five incident was another painful reminder of nuclear devastation, which in turn escalated fear towards nuclear fallout, food contamination, and other side effects of nuclear testing. Perhaps the 1954 Gojira captures the ways in which the Japanese public viewed nuclear catastrophe as something that can happen over and over again. After all, Japan experienced nuclear tragedies through war and testing. And with such harrowing experiences, people were likely to believe that anyone can be a victim, anytime.

But in the US? With growing support for anti-nuclear testing all over the world, average Americans uniformly began to perceive nuclear war as a shared global threat. But at this point, US citizens were already adjusted to a lifestyle heavily influenced by the atomic age. Videos about civilian defense against nuclear attacks were a normal part of classroom activity. Every day, families would gather in living rooms and listen to news about the arms race. It was just part of life. Perhaps this is why the 1956 “Godzilla” emphasized a collective fear that humanity can eventually overcome.

Maybe, it’s a stretch, but these two interpretations of Gojira could help us understand two different nuclear realities during the 50s. Retelling the story may be a stylistic choice, but such decisions can also be influenced by the social and cultural perceptions of the time.

After all, we all have our monsters — to each their own.

[1] Gojira (ゴジラ), Dir. 本多猪四, Producer田中友幸, 東宝株式会社 (TOHO), 1954, Film, 97 minutes.

After its release on November 3rd, “Gojira” marked 9.61million visitors to theaters and 160 million yen (approximately $45,000 in the 1950s).

[2] Godzilla—King of the Monsters!, Dir. Terry O. Morse & Ishiro Honda, Producers Edmund Goldmand, Terry Turner, and Joseph E. Levine, Embassy Pictures Corporation, 1956, Film, 80 minutes.

Mr. Edmund Goldman saw Gojira at a Chinatown theater in Los Angeles, CA on April 27, 1956. He bought the rights to broadcast “Gojira” for $25,000. “Godzilla” made 2 million dollars and was exported to 50 countries worldwide, generating roughly 40 billion dollars. The U.S. “Godzilla” was also released in Japan on May 29, 1957.

Great article and topic!

This theme is even more interesting when you delve into the political symbolism of the monster, and its reflection in the Hiroshima an Nagasaki’s bombs:

http://www.historyvortex.org/GodzillaSymbolism.html

And an interesting video for Spanish speakers: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BJNNF4XgV40