I am speaking today in a language that is new – a language which I who have spent so much of my life in the military profession, would have preferred never to use. That new language is the language of atomic warfare.

-President Eisenhower, “Atoms for Peace”

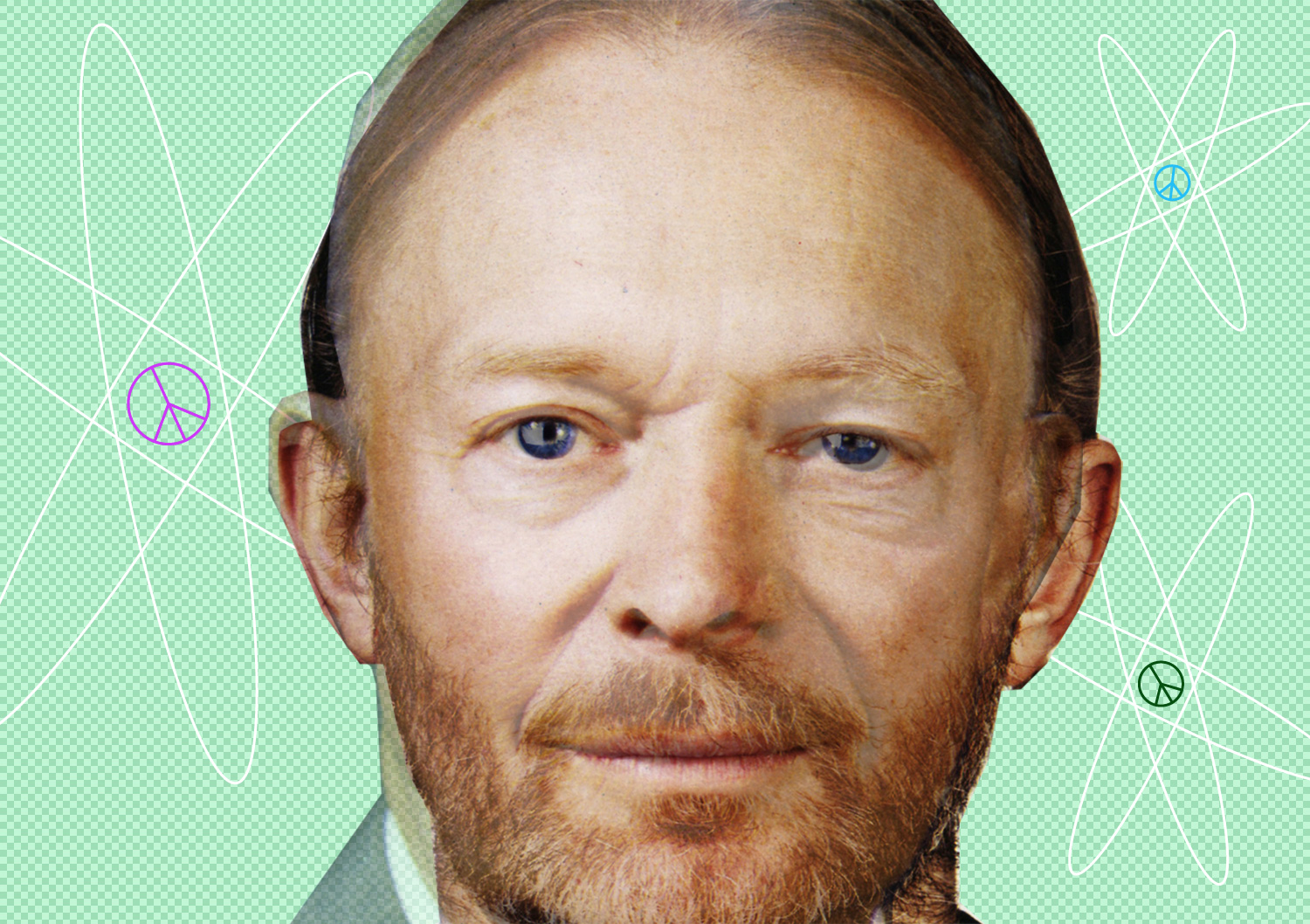

It was during undergrad when I was first introduced to Thom Yorke’s musical genius. Like many other kids at that time who thought their tastes transcended JT and Shakira, I considered myself refined for owning most of Radiohead’s albums and following faithfully when he released his side project, The Eraser. One of my favorite songs from that album is “Atoms for Peace.” With memorable lyrics (I want to eat your artichoke heart) and hints of experimental noise, it soundtracked my college years completely oblivious to the title’s subtle implications of Yorke’s emerging agenda to purge the world of nuclear weapons.

After releasing The Eraser, Yorke participated in a series of anti-nuke rallies, including Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament’s (CND) demonstration against the US ‘Star Wars’ missile defense system and Greenpeace’s Rainbow Warrior nautical tour , which started in 1971 to protest nuclear weapons testing. So it just made sense that he would name a song “Atoms for Peace,” a homage to the put-your-fist-up-against-nukes movement that has become a key element to his persona.

More recently, Yorke upgraded the “Atoms for Peace” concept to the moniker for his new band. Atoms for Peace (Yorke, Radiohead’s producer Nigel Godrich, Flea of Red Hot Chili Peppers, Mauro Refosco, and Joey Waronker) released AMOK last month, a debut album that blends Yorke’s trembling high vocals, electronic beats, and eerie instrumentals. Interestingly, they’ve included Nerth Nuclerek? Na Vynnav – Cornish for Nuclear power? No thanks. – on their website, which is a nod to the Smiling Sun’s anti-nuclear power logo. Saying “no” to nuclear power is far from embracing its peaceful potential.

Yorke’s vision of “Atoms for Peace” advocates leaving atoms alone. They are, after all, awesome and profound on their own. Yorke is among a steadily growing army of activists causing raucous against anything nuclear. Despite being pigeonholed as political hippies, these Greenpeacers and disarmament advocates have a very serious mission of representing a generation frustrated by its inheritance of nuclear technology.

I want you to get out and make it work.

– Thom Yorke, “Atoms for Peace”

1953 marked the first time an American leader spoke openly about living in the atomic age. US President Eisenhower’s “Atoms for Peace” speech explained the capability of the US arsenal, the fact that the atomic recipe is no longer a secret, and the need to create an institution that would manage nuclear material for the benefit of mankind. It was his way of telling the world that something good can come out of the rubble.

There is an incredible backstory behind this speech, one involving a grand scheme to stifle the Soviet Union’s quest for nuclear weapons. “Atoms for Peace” was part of Operation Candor, a media effort to tell the general public about the new perils of a nuclear world through a series of government-sanctioned speeches. Operation Candor wasn’t completely a gesture of transparency; there was an intentional juxtaposition of US (good ol’ guys) and SU (them communist villains) technical and organizational capabilities to demonstrate how much more advanced and responsible Americans were being with nuclear technology. With communist nuclear advancements snapping at US heels, it became necessary to neutralize Soviet Union’s nuclear aspirations.

But “Atoms for Peace” became so much more than a sappy speech; it presented a plan to ensure the responsible use of nuclear technology. President Eisenhower was passionate about establishing a system in which countries can “donate” nuclear material to an Atomic Energy Agency, which in turn would explore and promote peaceful uses of nuclear energy. He handwrote the juicy details of this idea on a typewritten draft and pledged US commitment to further investigate the feasibility of such agency. Almost sixty years later, we have the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) – the same agency that helped the UN handle Iraq when it was pursuing weapons of mass destruction back in the ’90s and Iran’s nuclear ambiguity today.

The “Atoms for Peace” speech and its proposal didn’t quite quell the arms race, but it was an attempt to engage the public in everything nuclear. Despite its underlying intention to outdo the Soviet Union, there was a genuine desire to re-imagine uses of nuclear technology. And in some ways, this was President Eisenhower’s way of navigating through an age of peril he inherited from his predecessor, President Harry S. Truman.

“Atoms for Peace” captures two opposite sentiments that share the reality of living in and coping with a nuclear world. We witness two influential people take very different approaches to global peace: one seeks to harness nuclear energy while the other aspires to banish it. But both concepts find commonality in their obscurities – the speech is a footnote in history textbooks the same way the band is considered a b-side to Radiohead’s epic career.

In the end, this is just another case study of policy versus pop. Which will influence more minds in the end? Perhaps both are too idealistic for us to ever know.

![Radio[active]heads: The Champions of “Atoms for Peace” Radio[active]heads: The Champions of “Atoms for Peace”](https://bombshelltoe.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/eisenhower-yorke.jpg)